Week 12: Categorical & Logistic Regression

Date: November 10, 2025

Today…

Final Project Prep

Some helpful tools (autosave & new library)

Regression Review

Categorical Predictors Review

Logistic Regression

Model Diagnostics 🤷

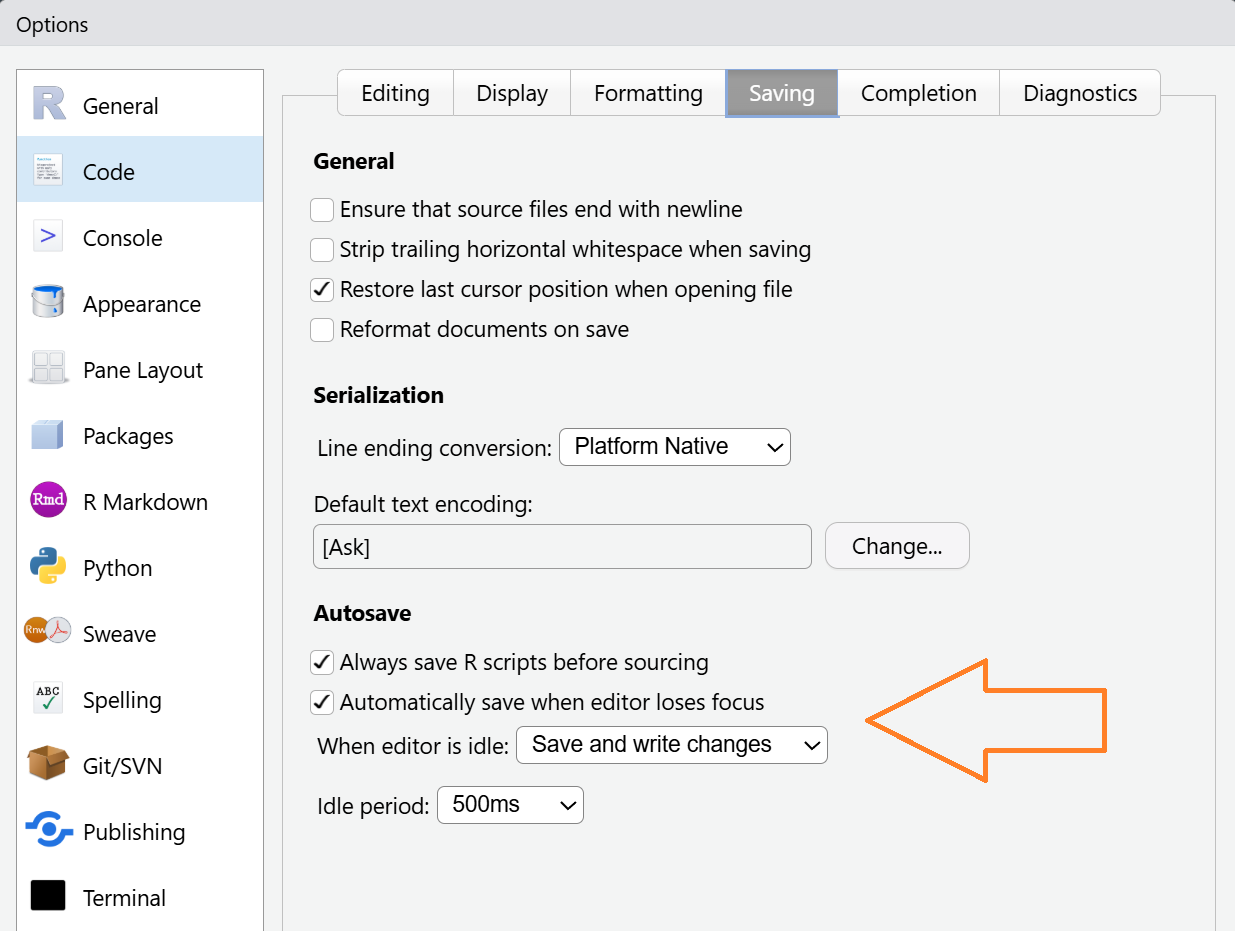

Autosave

Tools >> Global Options >> Code >> Saving

New Library: genzplyr

dplyr but make it bussin fr fr no cap

Regression does a vibe check on the data. lowkey draw a line through the points.

Regression

What is the equation for a regression??

Regression

\[ Y_i = b_0 + b_1X_{1i} + b_2X_{2i} + ... + b_nX_{ni}+ e_i \]

Regression

How do we interpret the regression coefficients (Intercepts & slopes)?

Regression

INTERCEPT: When all predictor variables are set to 0, our expected value (predicted \(\hat{Y}\)) will be this value.

SLOPES: For every 1 unit change in our \(X_n\) variable, there will be beta (b or \(\beta\)) units increase in our Y (outcome) variable, holding all other variables constant.

Explaining Variance

Explaining Variance

What do we do with categorical variables as predictors?

Categorical Predictors = factors

Typically identified by a grouping variable that may be a character

chr [1:1000] "Democrat" "Democrat" "Independent" "Republican" "Democrat" ...Need to change the variable from character to factor which will assign a number to each group

Dummy Coding (replacing factors)

Numerical placeholders used to represent categorical variables

Taking a categorical variable with \(k\) levels (e.g., Democratic, Independent, Republican) into \(k-1\) binary variables.

| political_affiliation | becomes | Ind (binary1) | Rep (binary2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democrat | –> | 0 | 0 |

| Independent | –> | 1 | 0 |

| Republican | –> | 0 | 1 |

| … | … | … |

Dummy Coding

For the variable with \(k\) levels, we use \(k-1\) binary variables…why not use all of them?

Including all three variables would result in perfect multicollinearity. All Democrats would be related to other Democrats and unrelated to everything else

By including 2 binary variables, we are able to obtain all information about group membership

Dummy Coding

The group that has 0’s for all the binary variables is the reference group

For interpretation, we will make our statements in reference to this group

| political_affiliation | becomes | Ind (binary1) | Rep (binary2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democrat | –> | 0 | 0 |

| Independent | –> | 1 | 0 |

| Republican | –> | 0 | 1 |

| … | … | … |

Categorical Regression

Going back to our Transformers dataset, let’s see how our political affiliation variable can predict # of transformers movies

Usually you have to create the separate dummy variables, but not in R. As long as your predictor is set as a factor, R will automatically dummy code the variable.

You can also double check the dummy/contrast coding

Interpretation

We are shown the different levels of our predictor variable, but you will not see a predictor for the reference group…this is the intercept!

Every interpretation is ALWAYS in reference to the reference group

Go to next slide for a pretty table

Call:

lm(formula = transformers ~ pol, data = cah_data)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.3447 -1.1804 -0.3447 0.8196 3.8367

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.18039 0.09399 12.559 <0.0000000000000002 ***

polIndependent 0.16434 0.12349 1.331 0.184

polRepublican -0.01713 0.14257 -0.120 0.904

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 1.501 on 799 degrees of freedom

(198 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.003244, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0007487

F-statistic: 1.3 on 2 and 799 DF, p-value: 0.2731Interpretation

Interpretation (text)

A linear regression investigated the relationship between political affiliation and number of transformers movies watched. Democrats showed a significant difference from 0 (b = 1.18, p < .001), but there was not a significant difference between Democrats and Independents (p = .18) or Democrats and Republicans (p = .90). The findings suggest that there are no significant differences between groups.

Note

How does this sound?

Changing the Reference Group

Maybe we want to compare to a specific group

We need to then update the reference group

Call:

lm(formula = transformers ~ pol2, data = cah_data)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.3447 -1.1804 -0.3447 0.8196 3.8367

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.34473 0.08011 16.786 <0.0000000000000002 ***

pol2Democrat -0.16434 0.12349 -1.331 0.184

pol2Republican -0.18146 0.13383 -1.356 0.175

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 1.501 on 799 degrees of freedom

(198 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.003244, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0007487

F-statistic: 1.3 on 2 and 799 DF, p-value: 0.2731lm() or aov() ?

We have the same setup between a linear model and a one-way ANOVA.

\[ Outcome_{continuous} = Predictor_{categorical} + error \]

Why would we pick one over another?

If we have a reason to have a reference group –> Regression

- Maybe we have a control group

If we just expect a difference somewhere –> ANOVA

- When you are predicting # movies from political affiliation

Everything is a linear model

Break ☕🍵🥐

Categories in Action (last time)

Goal: Gain greater familiarity with dummy coding and categorical predictors

Scenario: We are researchers examining the impact of a new intervention on reducing the vocalization “6️⃣7️⃣” in the youths. We have done classroom observations to collect data on how many times students say “6️⃣7️⃣” after receiving the intervention. Youths have been randomly assigned to one of 3 groups, and we need to determine which had the biggest impact.

Run the Regression with complete data

Note

Dr. Haraden needs to write the equation on the board 🧑🏫 Calculate the expected value for each group

Call:

lm(formula = post_score ~ group, data = six_seven)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5.000 -2.375 0.000 1.500 7.000

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 11.5000 0.9487 12.122 0.00000000000197 ***

groupOrange 1.5000 1.3416 1.118 0.2734

groupYellow 3.0000 1.3416 2.236 0.0338 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 3 on 27 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.1562, Adjusted R-squared: 0.09375

F-statistic: 2.5 on 2 and 27 DF, p-value: 0.1009Now what are the means for each group?

Now what are the means for each group?

Using R

Import dataset, include age and pre-scores to see how that changes interpretation

Warning

Dr. Haraden is going to start opening up R and doing a follow-along thing. You have been warned

Everything is a linear model

Introducing Generalized Linear Model

6️⃣7️⃣ Status

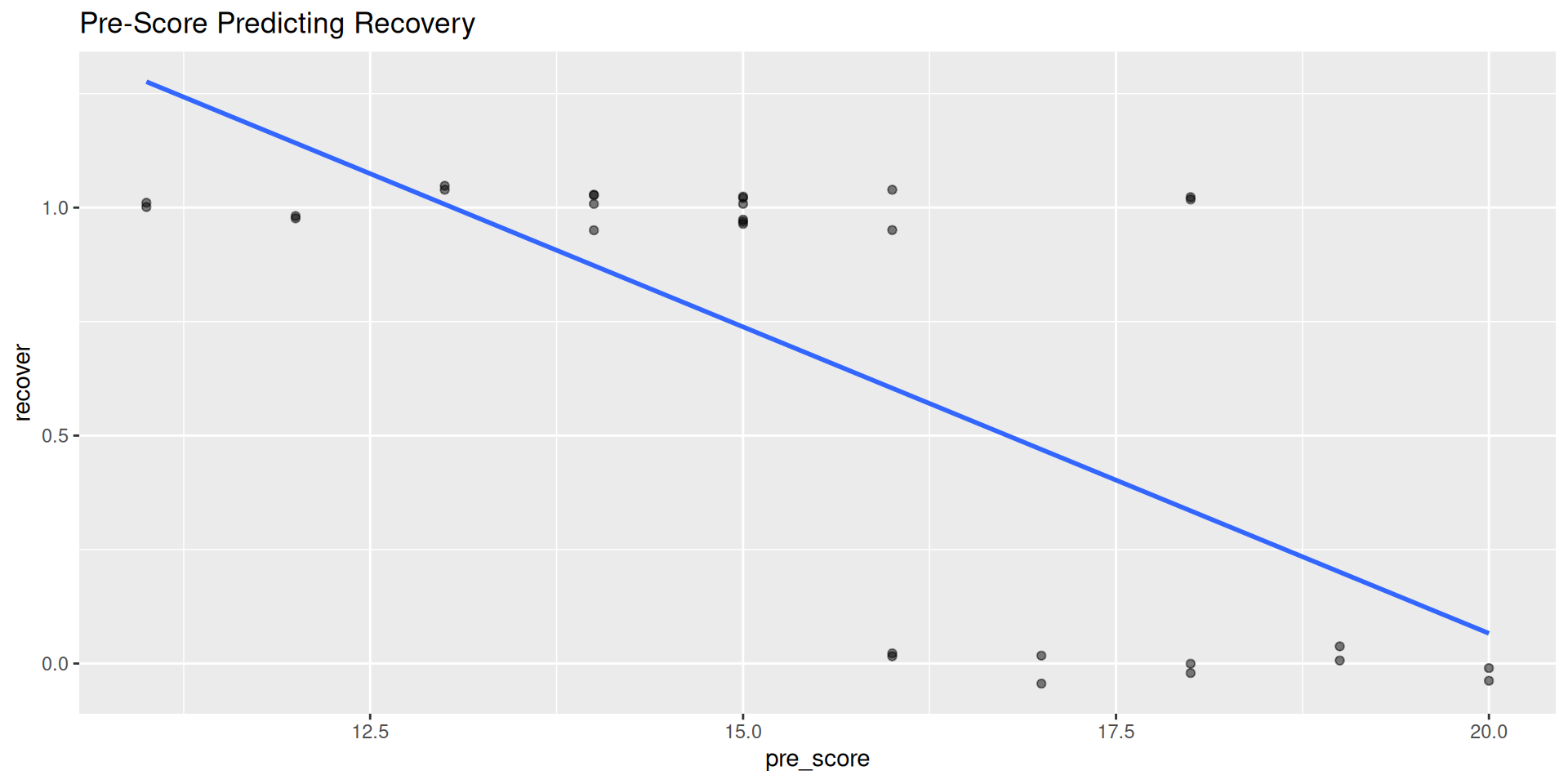

In our last example, we were able to see how these categorical variables could predict a continuous variable. This is perfect for linear regression.

What if we want to see if students have “recovered” from 6️⃣7️⃣?

We would then ask: “Which participants dropped below the clinical threshold for 6️⃣7️⃣ at follow-up? Now, our outcome is either recovered or not recovered.”

Recovery Status

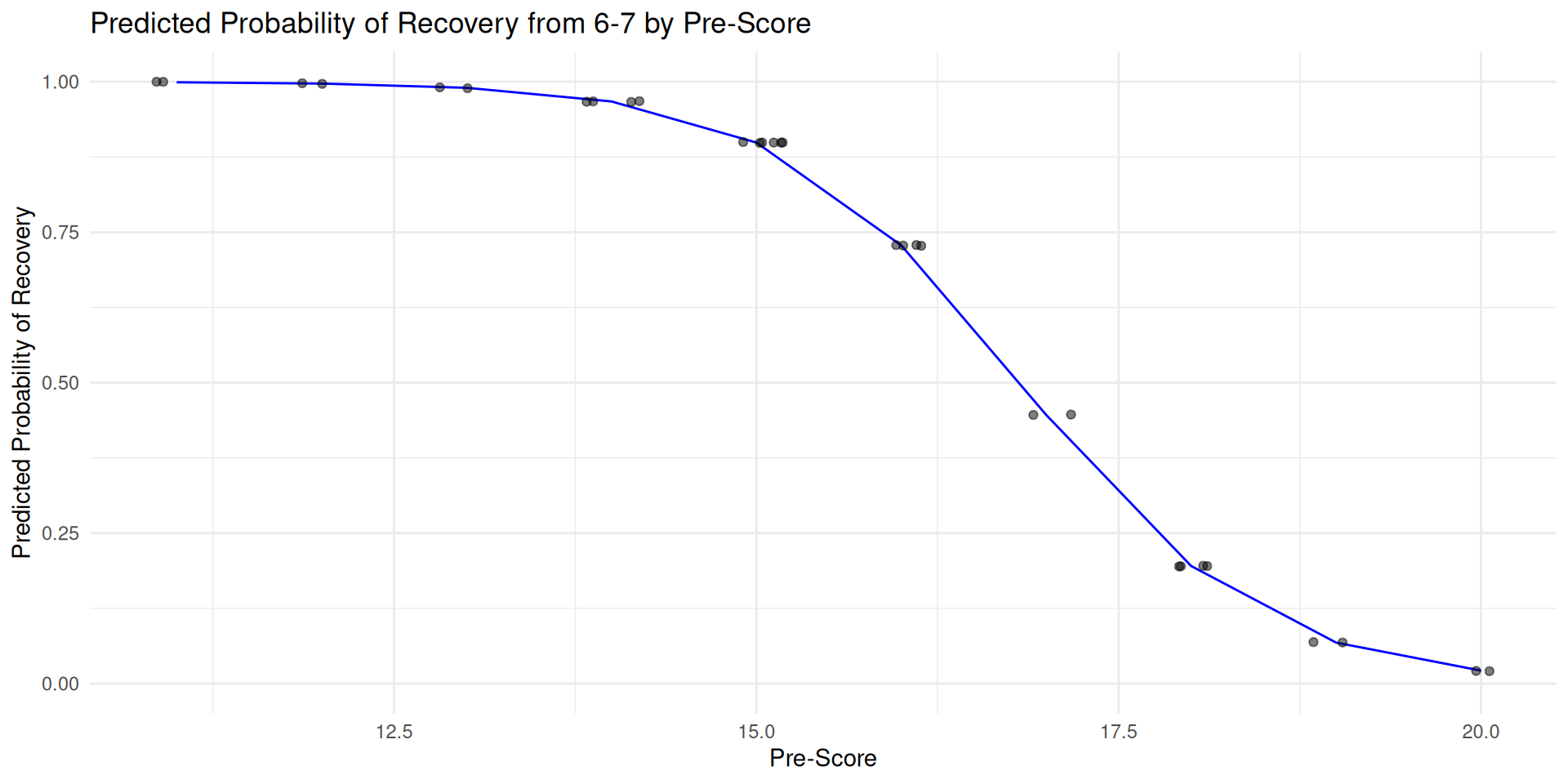

Now we have a binary outcome; Yes/No recovery

What happens when we fit a linear regression? What are the chances of someone with a pre-score of 12 recovering by the follow-up?

Recovery Status

Binary Outcomes in Regression

A simple line is not going to appropriately capture the data

- Plus, it definitely doesn’t make it a normal distribution! We only have 2 scores in our predictor variable…

Introducing Logistic Regression 🌟

- Using a logistic function we are able to better capture the data and get a “likelihood” or “probability” of an outcome

Probability to Odds to Log-Odds

Probability (p): The chance of an event happening. Ranges from 0 to 1

Odds: The ratio of the probability of an event happening to it not happening.

\(Odds = \frac{p}{1-p}\)

Ranges from 0 to ∞. An odds of 4 means the event is 4 times more likely to happen than not.

Log-Odds (logit): The natural log of the odds

\(Logit(p) = ln(\frac{p}{1-p})\)

Ranges from -∞ to +∞

Important

This step transforms our bounded outcome variable (0/1) to an unbound one!

Generalized Linear Model (GLM)

A generalization of a linear model (duh) that is used when the response variable has a non-normal error distribution

Most commonly used when there is a binary (0-1) or count variable as the outcome (we will focus on the binary)

Ultimately, we are trying to identify the probability of the outcome taking the value 1 (“success”) that is being modeled in relation to the predictor variables

GLM: Logistic Regression

\[ transformation(p_i)=\beta_0+\beta_1x_{1,i} + \beta_2x_{2,i} + \cdots+\beta_lx_{k,i} \]

We have to apply a transformation to the left side so that it can take variables beyond just 0 & 1

A common transformation is the \(logit\ transformation\)

\[ \log_{e}\left( \frac{p_i}{1-p_i} \right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1,i} + \beta_2 x_{2,i} + \cdots + \beta_k x_{k,i} \]

Recovering from 6️⃣7️⃣

Now we have a tool to figure this out, let’s see if the pre-score can predict recovery!

GLM - 6️⃣7️⃣ Data Interpretation

Note

Interpretation is still the same as linear regression, except we are dealing with log-odds of the outcome. What does that mean??

Call:

glm(formula = recover ~ pre_score, family = "binomial", data = six_seven)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 20.1873 7.0700 2.855 0.00430 **

pre_score -1.2002 0.4268 -2.812 0.00492 **

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 38.191 on 29 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 18.216 on 28 degrees of freedom

AIC: 22.216

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 6GLM - 6️⃣7️⃣ Data Interpretation (tables)

We want to be able to interpret these coefficients more easily so we put them into Odds Ratios

sjPlot is always coming in with the good tables

Odds Ratios (OR)

OR > 1: The predictor increases the odds of the outcome. (e.g., OR of 2.5 means the odds of believing in ghosts are 2.5 times higher).

OR < 1: The predictor decreases the odds of the outcome. (e.g., OR of 0.4 means the odds of believing in ghosts are 60% lower).

OR = 1: The predictor has no effect on the odds of the outcome.

Visualization

Extract the model implied probabilities for each individual

Plotting the predicted probabilities

probs %>%

ggplot(aes(pre_score, .fitted)) +

geom_line(color = "blue", linewidth = 0.5) +

geom_jitter(width = 0.2, alpha = 0.5) +

labs(

title = "Predicted Probability of Recovery from 6-7 by Pre-Score",

x = "Pre-Score",

y = "Predicted Probability of Recovery"

) +

ylim(0, 1) + # Keep the y-axis bounded at 0 and 1

theme_minimal()

Logistic Regression: Summary

| Feature | Linear Regression | Logistic Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Continuous | Categorical (Binary) |

| Equation | \(Y=β_0+β_1X\) | \(ln(\frac{p}{1-p})=β_0+β_1X\) |

| Key Interpretation | \(\beta_1\) is the change in the mean of Y | \(\exp(\beta_1)\) is the odds ratio |

| R Function | lm() |

glm(..., family="binomial") |

Break ☕🍵🥐

Next Up…

Follow along to apply these methods to a new dataset!

Predicting the probability of believing in ghosts. Hopefully we have time to go through this example 👻